Engineers are embracing Bluetooth to build robots that are cheap, smart and free from the wire ties that bind.

Bluetooth

is finally taking off. Literally. A small robotic blimp floats gently

through the Autonomous Systems Laboratory at the Swiss Federal

Institute of Technology, wirelessly interacting with a desktop computer

to literally evolve

its own navigation software without human intervention. What the blimp

sees via its onboard sensors is Bluetoothed to the PC for processing.

The artificially evolved "brains" are then transmitted back to the

mylar blimp so it can intelligently fly through its environment,

improving with each run. Bluetooth

is finally taking off. Literally. A small robotic blimp floats gently

through the Autonomous Systems Laboratory at the Swiss Federal

Institute of Technology, wirelessly interacting with a desktop computer

to literally evolve

its own navigation software without human intervention. What the blimp

sees via its onboard sensors is Bluetoothed to the PC for processing.

The artificially evolved "brains" are then transmitted back to the

mylar blimp so it can intelligently fly through its environment,

improving with each run.

While Bluetooth

has been slow to catch on for mainstream applications, engineers in

many research labs and garages around the world are leveraging the

wireless technology for future generations of small mobile robots and

"self-deploying" sensor networks.

"Until recently, Bluetooth has been a bit confusing for consumers," says Bryan Hall, a professional Bluetooth engineer at A7 Engineering

and robotics hobbyist. "In the laboratory though, people are more

willing to put up with tech warts. So you can now get these sensory

devices running around relatively quickly and spend your time writing

complex applications for them."

As an inexpensive wireless

option, Bluetooth provides many advantages for robotics designers over

other standards. First of all, it's low-power, so it doesn't guzzle

batteries like many other wireless technologies.  That's important, say, for small robots where every ounce counts -- an

aerobot, for example, like the blimp or the Bluetooth-equipped microrobotic helicopter recently demonstrated by Seiko Epson Corporation. Bluetooth is also robust. The specification

smartly contains several schemes that confirm whether a data packet

made it to its destination untainted, and resends it if not. This gives

roboticists the peace-of-mind that their machines can chit-chat

uninterrupted as long as they're in range of one another.

That's important, say, for small robots where every ounce counts -- an

aerobot, for example, like the blimp or the Bluetooth-equipped microrobotic helicopter recently demonstrated by Seiko Epson Corporation. Bluetooth is also robust. The specification

smartly contains several schemes that confirm whether a data packet

made it to its destination untainted, and resends it if not. This gives

roboticists the peace-of-mind that their machines can chit-chat

uninterrupted as long as they're in range of one another.

"If you need low power and high error recovery, Bluetooth is the natural way to go to replace wires," says Jean-Christophe Zufferey, the lead graduate student on the robotic blimp project.

Right now, Zufferey, professor Dario Floreano

and their colleagues are working on a Bluetooth-enabled robotic plane

that also flies indoors. The 30-gram aerobot is outfitted with a tiny

Bluetooth module to keep it in contact with its full-blown PC companion

while allowing it to soar. Like the blimp, and a wheeled and wired

robot before it, components of the plane are based on mother nature's

ingenious engineering. The control system consists of a computer vision

system, inspired by an insect's eyes, combined with so-called neural

networks. Following Darwin's "survival-of-the-fittest" model, the

computer runs an evolutionary process where the best code for the job

emerges out of the virtual gene pool. Bluetooth enables the robot to

evolutionarily adapt to its surroundings untethered from the PC driving

the unnatural selection.

Of course, once the aerobots emerge

from the laboratory for applications like traffic monitoring or

search-and-rescue missions, Bluetooth may not be the ideal wireless

solution. Most Bluetooth modules provide a range of just ten meters.

Others can reach ten times farther, but consume far more power.

Finally, the Bluetooth specification calls for just one megabit of

bandwidth, far too little for telepresence.

Bluetooth's short range and low-bandwidth is less of a problem for professor Walter Potter of the University of Georgia's Artificial Intelligence Center. A few months ago, Potter and his graduate students published a scientific paper demonstrating a new way for robots to communicate and, amazingly, collaborate using Bluetooth.

In

his demonstration, two small mobile robots collaborated on a "honeybee

task," meaning they worked together like insects to locate a target in

a room. The honeybee reference is based on the way each worker bee,

when it discovers food, directs other bees in the hive to the treat. In

Potter's experiment, the robots searched for a lightbulb in a large

room.

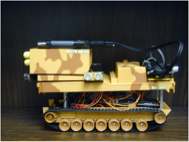

The robots were based on a commercially available

robotics kit that typically carries a Palm device as its onboard

microprocessor. Potter and his team decided to outfit their bots with

Compaq iPAQs specifically because of the PDA's Bluetooth capabilities.

While Bluetooth may not offer the security necessary for the military

search-and-destroy missions Potter has in mind, the technology, he

says, is incredibly useful for proof-of-concept demonstrations of "hive

robotics" systems. The idea is that many small simple robots are more

effective than a single complicated robot. If one breaks, the others

pick up the slack. Coordination is key, especially as the number of

robots on a team increases.

While Bluetooth may not offer the security necessary for the military

search-and-destroy missions Potter has in mind, the technology, he

says, is incredibly useful for proof-of-concept demonstrations of "hive

robotics" systems. The idea is that many small simple robots are more

effective than a single complicated robot. If one breaks, the others

pick up the slack. Coordination is key, especially as the number of

robots on a team increases.

"If the communication system is

robust and reliable, then the loss of one of the team members will only

have a minor effect on the outcome of the task," he says. "The

remaining robots could adapt their behavior based on the realization

that one robot has been lost...This is particularly advantageous in our

military-like scenario, where it is almost guaranteed that several of

the robots will be lost before the task is complete."

The next

step, Potter explains, is to enable the system to track moving targets

and also jack up the Bluetooth functionality so that if a robot goes

out of range by accident or to conduct independent reconnaissance, it

can "reconnect seamlessly and easily to the rest of the group" upon its

return.

Rate this article

by clicking on - or +

|

|

Discover Bluetooth devices? More like "discover new droids."

|