CSCI

1210

Economic Models – a brief overview

Introductory

Example:

In early

2003 President Bush proposed a massive, multi-year tax cut. He described this

proposal as a badly needed economic stimulus

package.

His political opponents in the Democratic Party

described the proposal as an unconscionable

giveaway to the rich.

Conservative commentators responded that these

criticisms amounted to class-warfare rhetoric.

How can we evaluate these claims? Is it possible to judge on the basis of

economic theory, or is this purely a subjective question of values?

Some

specific questions:

1.

How

much tax benefit will the average person receive?

2.

Will

the majority of the benefits go to rich, poor, or middle-class taxpayers?

3.

How

much will the tax cut stimulate the economy in the next year?

4.

What will be the long-term effects on

the economy and budget deficits?

5.

Is

it a good idea to stimulate the economy?

6.

Is

it OK if most of the benefits go to wealthy taxpayers, or is this unfair?

How we

answer these questions:

(1-2)

These are considered questions of fact;

we have confidence that they can be accurately answered using Government

economic statistics.

(3)

This is a projection using economic

models; it is fairly non-controversial

(4) This is also a projection, but

the models are controversial. It should be a question of fact, but it is not!

(5)

This is a value judgment, but non-controversial. Almost everyone agrees more

economic growth is good at this time

(6)

This is a highly controversial value judgment.

Some

interesting questions involving economic models:

1.

Effects

of medical cost inflation

2.

Average

income vs. income inequality

3.

Keynesian

vs. supply-side economics

4.

Cost

of mitigating global warming

5.

Future

of Social Security and Medicare

Effects

of medical cost inflation

In

recent years medical costs have consumed an increasingly large portion of our

total national income (Gross Domestic Product). Here is a worksheet for investigating this. Try these

scenarios:

1.

GDP

grows at 4.9% year and national health care costs grow at 7.4%

2.

Salary

grows at 2% per year and health insurance premiums grow at 7.4%

3.

Salary

grows at 2% per year and health insurance premiums grow at 10%

Click to see the full text of the US

government report from which these estimates are taken

Average

income vs. income inequality

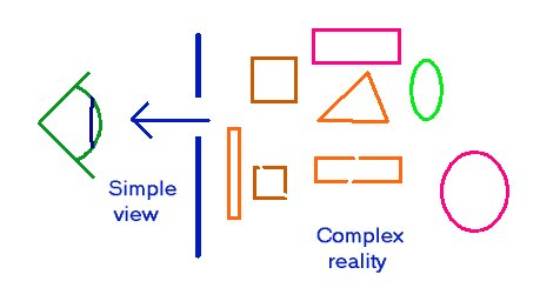

Economic statistics are like a keyhole through which we view the vast complexity of economic data.

The

average is a simple linear model that tames the complexity of the real world.

Sometimes important details may be lost – see the “Inequality” tab of the

worksheet above.

Do

you choose to view income through the “average” keyhole, or try to see the

details? It depends on:

1.

How

much detail you can tolerate;

2.

Whether

you think inequality is important;

3.

Whether

you think the details help or hinder the point you are trying to prove.

Keynesian

vs. Supply-side economics

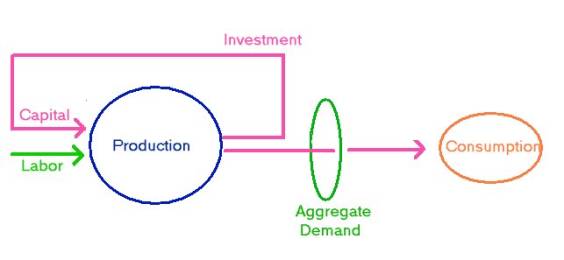

The

basic factors of production are labor and

capital. We will leave technology out of

this simple model.

Demand

is people wanting to buy stuff, which encourages producers to make it.

Two theories on how to increase production:

1.

Increase

aggregate demand (Keynesian economics,

after John Maynard

Keynes, 1883-1946)

2.

Increase

the supply of labor and especially capital (supply-side

economics)

How to

increase aggregate demand:

1.

Tax

cuts to people who will spend it

2.

Government

spending

How to increase

supply:

1.

Tax

cuts to people who will save it

2.

Eliminate

welfare, encouraging people to work

Which theory is more correct?

The

answer should be a scientific question, but in reality tends to be an ideological one! (People favor the theory that

best fits their political viewpoint)

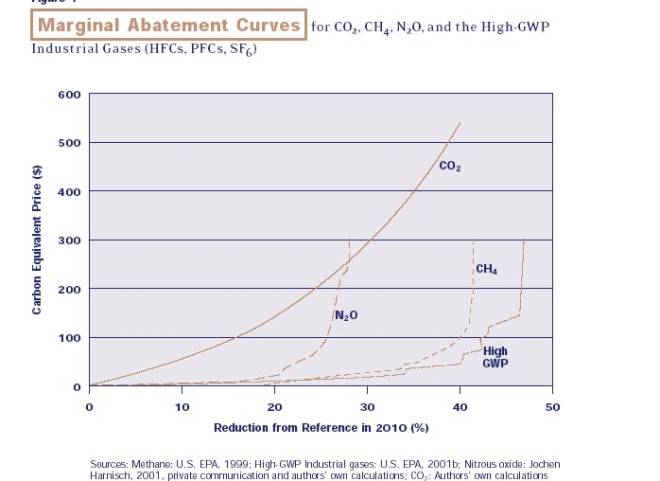

Costs

of Mitigating Global Warming

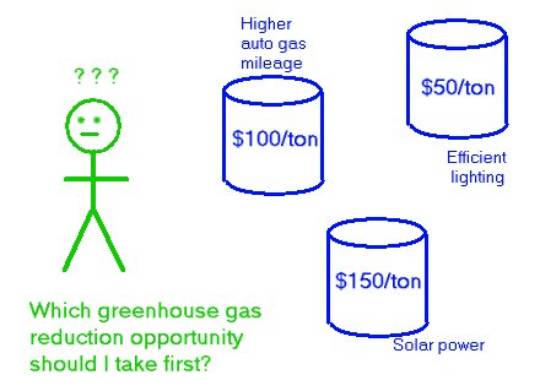

This graph from the report, Multi-Gas Contributors to Global Climate Change by the Pew Charitable Trust, deals with the marginal costs of reducing greenhouse gasses.

A ‘rational

person’ would pick the cheapest opportunity to save carbon first, then the next

cheapest, etc.

The marginal cost of the first batch of carbon saved: $50/ton

The marginal cost of

the second batch of carbon saved: $100/ton

The marginal cost of the third batch of carbon saved: $150/ton

n As Mr. Economic

Man is forced to choose more and more expensive opportunities, the marginal

cost goes up. Perhaps, it is better to choose some other gas besides C02.

n This “bottom-up”

model predicts a low cost for avoiding global warming. Other ‘top-down’ models

predict a higher cost.